New Zealand Spinach (Tetragonia tetragonioides or expansa (Pall.) Kuntze) in the Medical Museum garden. In Maori, the plant is known as kōkihi, in English also as Cook’s Cabbage, Botany Bay Cabbage or, in Australia, Warrigal (wild) Greens. Photography by Tereza Vobecká

Gregor Johann Mendel and His Greens: for the 200 Anniversary

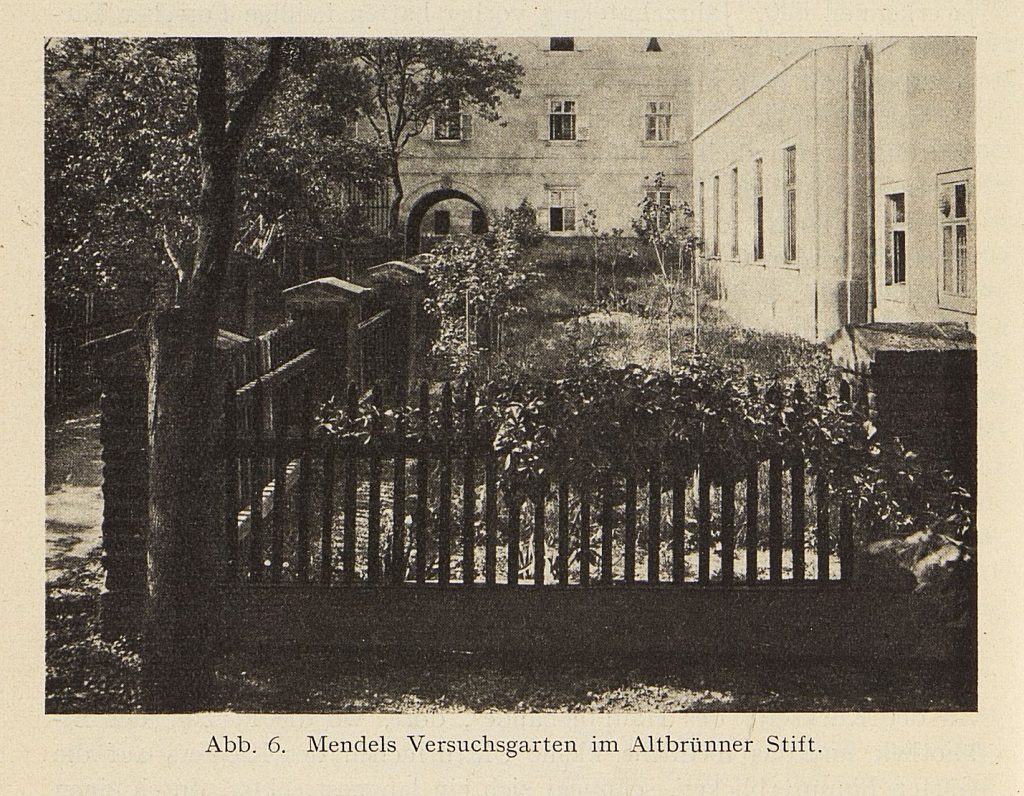

On July 20, 2022, we commemorate 200 years from the birth of the founder of genetics, the Moravian naturalist Gregor Johann Mendel (1822-1884). After studies in Brno and Olomouc, Mendel, an Augustinian monk, took his priestly vows, but he showed greater interest in scientific work than in a spiritual path and started teaching as a substitute at the Gymnasium in Znojmo in 1849. In the early 1850s he continued studying natural sciences in Vienna in order to find a full teaching job, but he did not pass the exams. Between 1854 and 1868, when he was elected Abbott of the St. Thomas Abbey in Brno, following the death of Cyril Napp (1792-1867), he taught physics and natural history at the Realgymnasium in Brno. In the years 1854- 1863 he performed the famous experiments with cross-breeding of pea plants, whose results he published in the proceedings of the Brno Natural Science Association in 1866. Mendel showed that in the first generation of hybrids, only dominant features manifest: the plants have hybrid genetic makeup (genotype), as they inherited factors from different parents, but share the same appearance (phenotype). In the next generation, the plants that inherited only dominant forms or a mixture of dominant and recessive forms exhibit dominant features (such as yellow color or round shape of the seeds), only those that received recessive forms from both parents, have green or wrinkled seeds. In further generation, the distribution of traits follows mathematical rules of combination. Different traits – the color of the seed, its shape, the color of the pod or the placement of flowers on the stem – are inherited independently.

Mendel was not inspired only by theoretical concerns: he was an avid gardener and a reader of books on growing of fruit and flowers, as well as beekeeping, from the monastery library. Following his predecessor, the Abbot Napp, he joined the Moravian-Silesian Society for the Promotion of Agriculture, Natural Science and Geography in Brno (K. k. mährisch-schlesische Gesellschaft zur Beförderung des Ackerbaues, der Natur- und Landeskunde) and later both the Natural Science Association (Naturforschender Verein) and the Moravian Association for Pomology, Viticulture and Horticulture (Mährischer Obst-, Wein- und Gartenbau-Verein) in Brno, he served as a judge at annual agricultural exhibitions and as an examiner of fruit-growing courses. His cross-breeding experiments were not limited to peas and beans, but included corn and a variety of flowers. He applied the results in growing pulses and vegetables in the monastery garden for food. An article published in the Mährischer Korrespondent, as reprinted in the Neuigkeiten newspaper in Brno (July 26, 1861) reports: „The M.K. brings the following account, of interest to garden owners as well as flower growers: P. Gregor Mendel, a Professor at the Gymnasium here, pursues very instructive experiments with the aim to improve the varieties of both flowers and vegetables in our region. [His efforts] deserve attention as they significantly promote an important trade sector in the suburbs. Artificial insemination can offer truly surprising results. The vegetables grown by the Professor, whether it is peas, green beans, cucumbers or beans, are tall and give abundant fruit, whose taste and size leave nothing to be desired. The seeds used for growing these plants were mostly imported. Among foreign vegetable species, the New Zealand spinach [Tetragonia expansa] acclimated well and thrives in our soil. Not only do its unusually fleshy leaves contain more nutrients than the common sorts, but the whole plants grow exuberant enough to cover, in some cases, the whole expanse of the experimental patch. Experiments with potatoes have not been so successful thus far.”

Others are more qualified to tell the history and the significance of Mendel’s discoveries in his anniversary year. In the Medical Museum, we have chosen a slightly more frivolous way to celebrate the bicentennial. We have sown and – in the skillful hands of Tereza Vobecká – continue to grow several plants of the New Zealand spinach that wholly occupied its assigned patch in Mendel’s garden and greatly improved the fare of his confreres. Recipes for preparing this vegetable are usually limited to stating that “it is prepared just as regular spinach.” The plant was discovered by Joseph Banks (1743-1820), the botanist of the 1770 James Cook expedition, at the Queen Charlotte’s Sound in New Zealand and the crew of the Endeavour „has boiled and eaten it as greens.“ Banks introduced it into England in 1772. Its leaves remained „fit for use“ during the driest summer months and into early fall, when regular spinach grows seeds and is no longer tasty. The plant ran wild in Europe around 1918.

In her famous Practical Cook Book, first published in 1845, Henriette Davidis (1801-1876) writes: „The big, fat leaves that unfold very quickly when warm, supply abundant portions for the kitchen and are prepared as spinach. Or we can tear the leaves from their stems, cook them, wash them and crush them with a ladle, cut them a few times across, add some kidney fat and flour and stir with flour and some butter into a creamy sauce, season with salt and some nutmeg and stew for a while.“

We have started late and the leaves of our spinach plants remain small: but the season is not over yet. Do you happen to have a good recipe for preparing the greens favored both by Cook and by Mendel?