Stoneware Pharmacy Vessel Inscribed “Elect[uarium] theriac[a]”, Germany, Early 1900s. NML Medical Museum Pharmacy Collection, PH 30

Object of the Month: July 2022

Theriac

From the Exhibition Plagues 1521-2021 in the NML Medical Museum

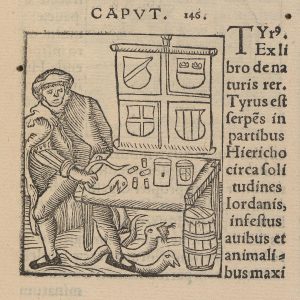

Manufacturing theriac from snakes. Woodcut (1536) from the book De animalibus, Bartholomeus Anglicus (1203-1272), De proprietatibus rerum, Liber 18. Wellcome Images.

Stoneware medicinal jar inscribed with Elect[uarium] theriac[a] in the Museum collection, was made from early 20 century Germany. Theriac, a universal remedy to cure both illness and poisoning and secure lasting health, is normally associated with more remote history. Some medicines that boast of their antiquity have remained in the supply of apothecaries and the demand of the sick much longer than we would expect.

The word “theriac” (treacle) comes from the Greek thérion, animal, beast, or snake. The complicated mixture of both salubrious and poisonous substances blended with honey to make a thick, viscous liquid (electuary) was originally used against poisonous bites and stings as well as intentional poisonings. King Mithridates of Pontus, in the 2nd century BCE, dreading assassination, supposedly invented a famous mélange of figs, nuts, rue, and salt that bears his name, mithridatum. Physicians added dozens of further ingredients: the recipe of Aurelius Celsus (1 century CE) lists 36 components. No less popular theriacum andromachi, allegedly devised by Andromachus the Elder, personal physician of Nero, and described by Galen in the 2 century, contained over sixty substances including snake meat, Lemnian soil (terra sigillata), and a much larger proportion of opium. In the Middle Ages, theriac served against both poison and the plague, later also against syphilis. It was supposed to cure fever, inner swellings and injuries, improve digestion and sleep, relieve heart ailments, and counteract bites of snakes, scorpions, or rabid dogs. Regular use granted permanent youth. Much of the relief provided was due to opium: Christophorus de Honestis warned against opium-containing medicines as early as 1370.

Many materials used in the making of theriac were hard to obtain and came from exotic countries. The process of production was complex and the mixture “matured” for years or decades. The procedure of combination and maturation could only be learnt by experience. This inspired substitutions if not straight-out falsifications. Pharmacists could make theriac only under the supervision of a physician, the process was public (“Theriak-Schau” was obligatory until the 18 century) and the vessels were marked with hallmarks. Pietro Mattioli (1501-1577) warned against false antidotes on offer by charlatans and suggested one only buy theriac from Francesco Calzolari (1522-1609) of Verona. As many of the original elements, used in antiquity, were no longer available, Mattioli designed his own specialties with similar effects, namely the “scorpion oil,” also from Calzolari’s pharmacy. The simple recipe for mithridatum in the Czech selection from Mattioli’s Herbarium (1595) does not use honey: crushed leaves of rue, juniper seeds, and figs are mixed with rose or wine vinegar.

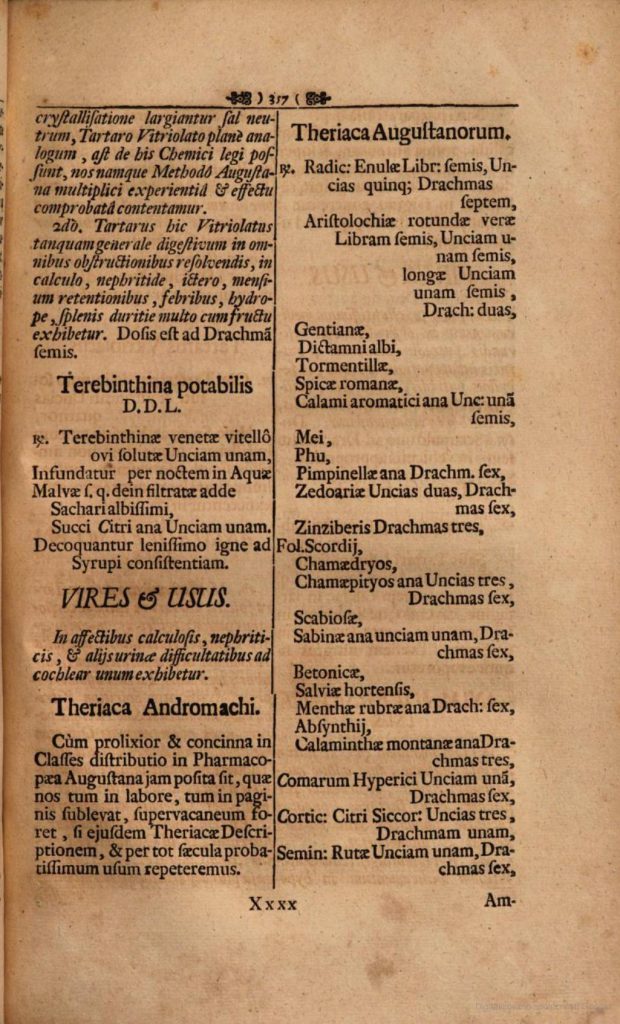

The 1739 Dispensatory of Prague leaves out theriaca andromachi, described in many other pharmacopeias, listing instead a simpler Augsburg

Tin vessel for Venetian theriac marked on the lid, Venice, 1603. Science Museum London, Wellcome Images

theriac, a theriaca smaragdina containing precious

stones, chips of ivory, and unicorn horns, or theriaca coelestis with bezoar. A simple four-part (diatessaron) theriac contained laurel leaves, birthwort, gentian root, and myrrh, crushed and mixed with honey. Even more accessible was the “poor man theriac” (theriaca rusticorum) mentioned already by Galen, garlic. The Venetian theriac, marked with the stamp of the Republic of Venice, was imported into most European countries including the Czech lands: today, the metal seals of Venetian vessels, found by metal detectorists, remain valued collector items. In the Western Bohemian town of Eger, a mithridatum egrensis was authorized by the town council until 1823.

In the 17 century, the progress of natural sciences contested the effect of this panacea. Chemist and physician Jan Baptist van Helmont (1580-1644) ridiculed it as an obsolete quack remedy, mixed by priests and charlatans in the hope that among the hundreds of components one will accidentally work. The pharmaceutic textbook published by the Prague doctor Simon Tudecius in 1695 mentions theriaca andromachi more than twenty times as a cure for many diseases, the 1699 supplement not even once. In the 18 century it was withdrawn from some pharmacopeias. Meanwhile, the production and import of theriac remained under state control. An 1816 Imperial Resolution and an 1846 Court Decree granted import and distribution of Venetian and Trieste Theriac in Austria exclusively to qualified pharmacists, based not on its inefficacy, but its toxicity. The struggle of the enlightened state authorities with quackery included the fight against Theriakkrämer, theriac chandlers, as well, especially in the eastern parts of the monarchy.

Theriac in the 1774 Austrian Provincial Pharmacopeia omitted snake poison or meat but names 57 component parts. In 1794, the number of ingredients fell to 16 (alongside four-part diatessaron), in 1869 to eight. „Stomach electuary“ or „aromatic electuary“ with honey, mint and sage leaves, angelica and ginger root, cloves, and nutmeg was mixed with opium in the ratio 120:1. The 1872 German recipe replaced ginger and angelica with gentian, valerian, and birthwort roots and adds myrrh, cinnamon, cardamom, sherry and vitriol of iron: both prescriptions agreed on opium, cinnamon and honey. Theriac (electuarium aromaticum cum opio) anished from the codex in Germany in 1882, in Austria in 1889, in France only in 1908. It remained available as an unofficinal medicament: pharmacists could prepare it on demand, assuming they kept to the last prescribed composition. Other preparations may have appeared on the market as theriac, perhaps including the „stomach electuary” without opium, which the Czech Pharmacy Board struggled to delist in 1896. The Mährischer Korrespondent admonished against using theriac in falsifying milk in 1871; theriac was also among the ingredients for „stomach brandy“ in Exemplary Housewife published by Julie Svobodova in 1879, together with gentian, saffron, and cognac. „Electuarium aromaticum cum opio“ still appearedin the Little Pharmaceutic Manual written by Jaroslav Kops (1916-1991) during the war and published in 1946. In Germany, it was listed the addenda to the pharmacopeia as late as 1953. Venetian theriac (with no opium) remains a component in the „Schwedenbitter“ (Swedish drops) cordial until this day.

The „electuarium theriaca“ jar in the Medical Museum collection is inscribed with red letters on white ground. On 20 century glass pharmacy vessels, labels with this color scheme designate separanda, poisonous substances to be stored separately: strong poisons (venena) are labeled with white letters on black. This color use supports the dating of the jar to around 1900.