Object of the Month: May 2024

“A Midwife’s Amulet”

At the end of April 1945, shortly before the liberation of Czechoslovakia and only a few days before his death, the gynecologist and numismatist Antonín Mastný (1875-1945) donated to the Medical Museum, “to honor the memory of Professor Emil Zikmund,” a pendant of silver chains and a thaler, decorated by small crosses and colored glass. Emil Zikmund (1874-1945), the Head of the Women’s Clinic at the Prague General Hospital and the Chair of the Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics, perished in an air raid on February 14.

Antonín Mastný helped to run the newly founded museum at least since 1936, he was elected to the Board in 1937 and appointed curator in December 1938. In 1941, he founded its numismatic collection. During the war, he gifted most of the collection of more than 600 coins and medals on medical themes he built over three decades to the museum, as well as books and other objects. Dr. Jan Tůma (1887-1949), another gynecologist among the founders of the Museum and a longtime acquaintance of Mastný, brought the news of the gift to the meeting of the Society on April 27, describing the pendant as an “unusual amulet (a thaler), worn by a midwife as part of an adornment with chains and color glass beads in the course of her work.” The Board of the Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics thanked Mastný and wished him a speedy recovery, but heart disease claimed his life as soon as May 2. The pendant became his last gift to the Medical Museum.

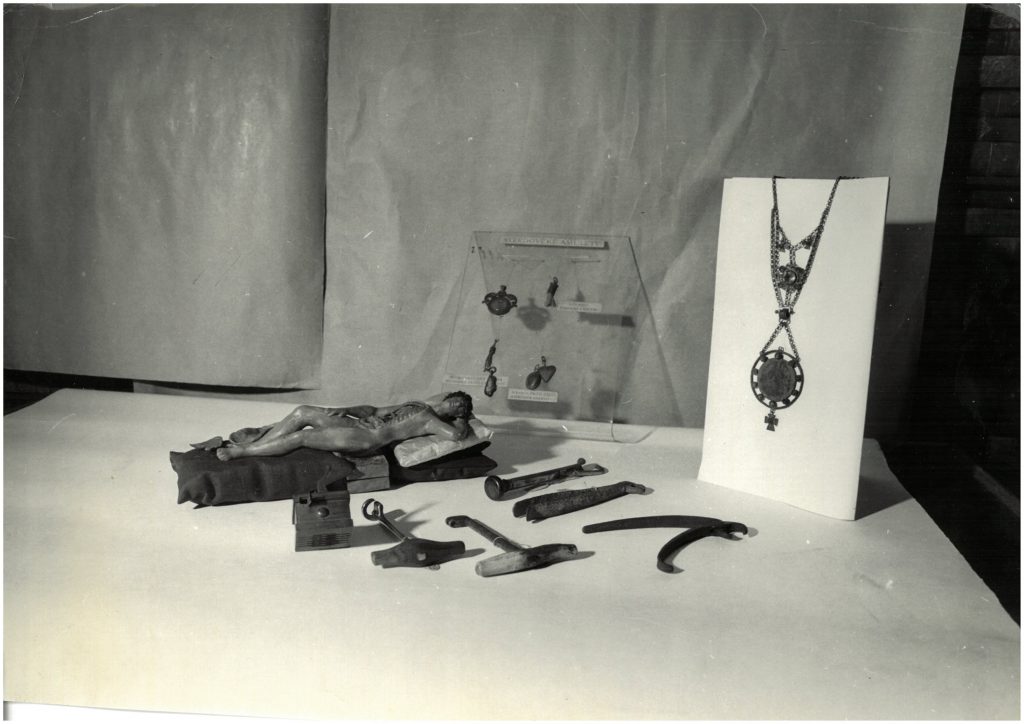

Medical Museum collections, Prague, October 1961, before the opening of the museum on Pařížská Boulevard. „Medieval amulets, lavishly decorated midwife badges, various anatomical models, dental instruments and others.“ NML Medical Museum Photography Collection, FA 3496

The assessment of the jewel as a “midwife’s amulet” probably originates with Mastný himself. The story of a midwife and her charm persisted in the 1960s inventory books, catalogues and exhibition photos. Mastný does not mention it in his 1924 article on Obstetricia in nummis (Obstetrics in coins); it appears neither in the lists of acquisitions published in the Bulletin of Czechoslovak Physicians, nor in Jaroslav Obermajer’s writings on Mastný and his collection. Mastný collected primarily coins and medals on medical themes: his identification may have been mere wishful thinking; on the other hand, he could have had information on the object now lost to us.

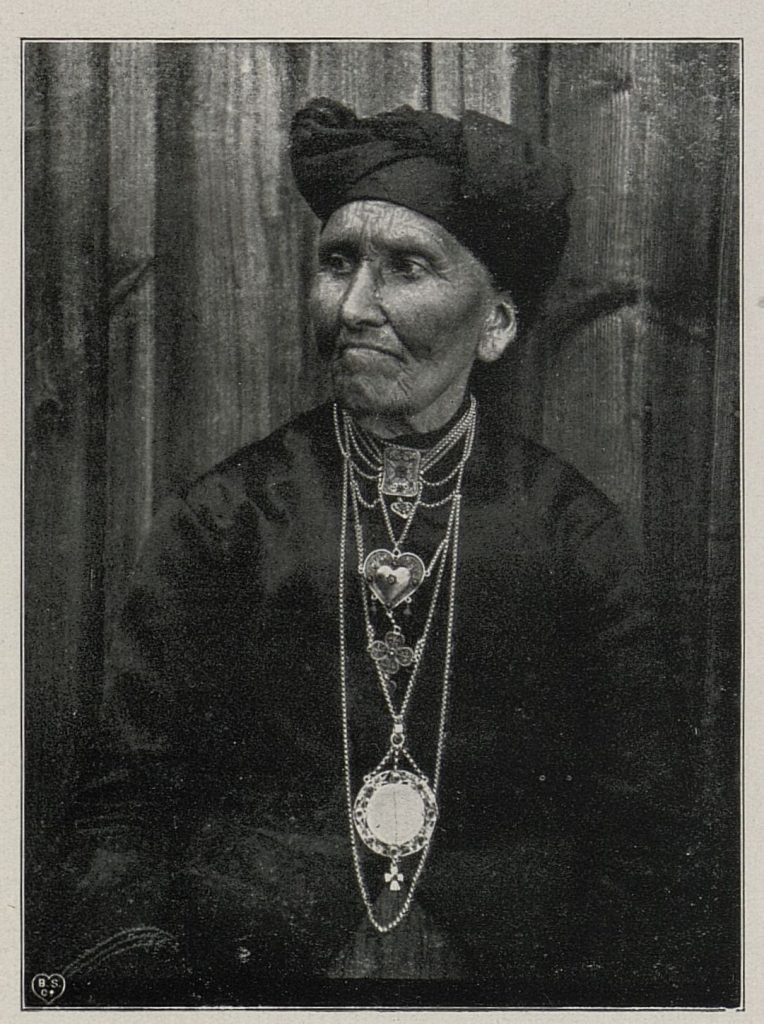

We can only wonder to what extent Mastný was aware of the origin of the “amulet.” In fact, it is a part of the 19th century traditional costume worn in the German-speaking borderlands of Western Bohemia, above all in the former Elbogen region. In German, it was known as Weiwatsg’häng (woman’s pendant) and in Czech as „loketský šperk“ (Elbogen jewel). Josef Hofmann marked Kynšperk (Königsberg an der Eger) as the western limit of their manufacture and use, in the south, they were known as far as Železná Ruda (Eisenstein) and Vimperk (Wittenberg) in the Strakonitz region. A variety of these jewels can be seen today in the Museums in Karlovy Vary and Cheb, the Elbogen Castle, the National Museum, and the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, as well as some German and Austrian collections.

Mommy in a traditional coat, with a thaler pendant around her neck, Western Bohemia, photograph from the late 19 century. Hofmann (1932), 56

We have, however, no evidence of midwives using them, whether as charms or as badges. Coin jewels did assist women in travail and newborn children: Mastný writes of devotional medals worn around the neck or sown inside clothing, of rosary chains with small medals of the Mother of Sorrows, of Matthias Corvinus ducat coin, possibly worn as an amulet by Hungarian woman in childbed. Infants received thalers and jewels made from them from their godparents. A coin given at childbirth served as ceremonial finery, financial security, a guarantee of the bond between the godfather and the godchild, but also a medium of magical protection. There is little data on how and when “Elbogen jewels” were obtained: the occasions included christenings, weddings and bequests, adult women had them made from coins kept in families. Midwifery insignia, whether badges of state-examined midwives introduced by the Empress Maria Theresa as early as 1753, pins issued to midwifery school graduates and association members, or medals awarded for assisting prominent childbirths or for years of successful work, were much simpler and in no way similar to the thaler pendant.

The “Elbogen jewel” consisted of three parts: the neckpiece (Fachla) made of several silver chains with two plates (Packla) to be tied with a silk ribbon at the nape of the neck; the pendant itself (G’häng) of chains joined in the middle with a metal loop with decorations; and finally a locket, a silver thaler or a twenty Kreuzer coin with the portrait of the Virgin Mary or Maria Theresa, or sometimes metal cross or a heart adorned with ornaments. The locket was often embedded in a circle of silver wire, mostly decorated with filigree, with smaller silver hangings known as Klampala or Klankala, after the sound they made when moving.

Specialized girdler (Gürtler) workshops in smaller West Bohemian towns made the pendants between the 1820s and 1870s for the use of village residents. Hence, their forms reflect both urban jewelry patterns and the preferences and needs of the customers. Some of the workshops (Kettengürtler), around 1860 in Chiesch, Mies, Luditz, Schlackenwerth, Königsberg or Dotterwies, specialized in making the chains of cheaper, unstamped silver, which they then sold by cubit to be processed further; others made the decorative loops and assembled the jewels. Silver blackened easily and for major holidays and other occasions, the jewels had to be cleaned, providing the girdlers with a regular source of income. More flamboyant pendants cost between 30- 45 guldens (corresponding today to 500-750 Euro), making them affordable only to affluent families. Cheaper products, with a thaler hung on one to three chains and with minimal decoration, could be purchased for 2 ½ – 10 guldens, about 40- 160 Euro today.

The neckpiece of the Medical Museum jewel is built of four silver chains; the five chains of the pendant join in rosette loop with a yellow glass faux stone and four red glass beads imitating topaz and garnets. Two small crosses pattées hang from the pendant, decorated with faux garnets as well. In folk costume jewelry, actual Czech garnets were an exception. From the locket, a silver Bavarian thaler in a circle with ten red glass beads is suspended, with a larger cross pattée with a faux garnet hung underneath. The chains are of the simpler Erbsenkette (“pea chain”) type, which displaced the more opulent “rose” and “plate” chains from the 1830s onwards. After 1870, ceremonial folk costumes in Western Bohemian regions all but disappear and among ornaments, factory-made costume jewelry takes over. The number of chains and fairly rich decorations suggest a medium-priced artifact, to be dated approximately to 1830- 1870.

The thaler of “convention currency” was legal tender in Austria, Bavaria, Saxony and other German states between 1753 and 1856. The obverse side of this particular coin shows the portrait of the Duke Carl Theodor II., the data 1778 and the signature of the Munich “iron cutter” (die maker) Heinrich Straub (1737-1782). The reverse carries an image of the Virgin Mary standing on the crescent moon (Assumpta, Mondsichelmadonna) among clouds and sunrays, encircled with the words Patrona Bavariae, Patron Saint of Bavaria. In the pendant, the coin is flipped over to present the protective image of Mary in the front. The motif is based on the “Woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet” of the Apocalypse (12.1-17), a theme common on medieval statues, paintings and initials, and later on crests and on coins. Bavarian coins carried the image of Mary on the crescent as early as 1625. An almost identical image is found on Theresian coinage minted in Hungary from 1740, with the text Patrona Hungariae. After 1797, when Austrian paper money was no longer convertible for silver, and especially after the state bankruptcy in 1811, owners withdrew silver coins from circulation. Older Austrian and German coins with higher silver content were kept and often preserved in jewelry.

Jewels featuring coins and metal chains with beads or stones were common beyond Western Bohemian borderlands. The heroine of the classic The Grandmother by Božena Němcová (1855), set in Eastern Bohemia, owned a thaler pendant with Czech garnets. In the Middle East and in Africa, thalers of the Empress Maria Theresia remained the means of payment until the 20th century; the portrait of the Empress was thought to bring good charm as well. Silversmiths from Bulgaria, Turkey, Yemen, Oman, or Ethiopia used these thalers for ornamental jewelry: their works remain the most precious objects of many museum collections.

The Elbogen jewel in the Medical Museum collection was probably misidentified from the outset. The object can, however, no longer be disentangled from the story that tells how it was donated, originally named, and later understood and links it with the museum and its history for all time. After all, can we be entirely sure it never belonged to a forgotten midwife?

Further reading:

Josef Hofmann, Deutsche Volkstrachten und Volksbräuche in West- und Südböhmen (Karlsbad: Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Heimatkunde und Heimatpflege im Bezirke Karlsbad, 1908, 2. vyd. 1932)

Josef Hofmann, Die Nordwestböhmische Volkstracht im 19. Jahrhundert unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Elbogner Kreises (Karlsbad: Im Selbstverlage des Verfassers, 1908)

Josef Hofmann, „Schmuck- und Prunkgegenstände im Osten der nordgauischen Sprachgebiets: ein Bruchteil meiner dasselbe Gebiet behandelnen, in Vorbereitung befindlichen Volkstrachtenkundes des 19. Jahrhunderts,“ Unser Egerland 10/4-5 (1906), 142-146

Alena Křížová, „Šperk příslušníků německého etnika v českých zemích,[Folk Jewelry of the German Ethnic Group in the Czech Lands],“ Folia ethnographica 52/2 (2018), 83-99

Alena Křížová, „Proměny tradice: loketský zlidovělý šperk [Transformations of the Tradition: the Elbogen Popular Jewelry],“ Národopisné aktuality 1 (2002), 40-43

Jiří Martínek, Šperk Loketska: katalog výstavy ze sbírek Karlovarského a Chebského muzea [Elbogen Jewels: a Catalogue of the Exhibition from the Collections of Museums in Karlovy Vary and Cheb] (Cheb: Chebské muzeum, 1987)

Marcel Paška, „Loketský šperk ve sbírkách Muzea Karlovy Vary, [Elbogen Jewels in the Museum Karlovy Vary Collection]“ XXIX. historický seminář Karla Nejdla: sborník přednášek (Karlovy Vary: Úřad města Karlovy Vary, 2020), 36-37

Jaroslav Obermajer, „Antonín Mastný (1875-1945), spoluzakladatel Lékařského muzea a Numismatické společnosti československé, [Antonín Mastný: a Co-Founder of the Medical Museum and the Czechoslovak Numismatic Society]“ Dějiny věd a techniky 4 (1995), 215-224