Reader, Beware! A Warning Issued by the Czech Relief Association for Lung Disease Victims, attached to the front endsheet of Jan Vana’s book Ideals of Science and Faith (Praha: J. Otto, [1912]). The instruction has libraries place the warning on the inside cover. That place may have been taken by a library sticker, replaced later with the one with a call number, an accession number and an etching we see on the left. NML Medical Museum, MA 3549

Object of the Month: March 2022

Reader, Beware: Books Not Licked Do Not Transmit TB

“To be pasted on the inside cover of a borrowed book! Reader, beware! (1) The borrower provides a clean paper cover for the borrowed book. (2) In the interest of public health, every reader is requested to report any infectious disease in the family to the library management, so that all borrowed books are suitably disinfected. (3) During the duration of the disease, no books are to be lent. (4) To protect against tuberculosis, the following is of note: (a) tuberculosis is an infection that resides in the lungs and the respiratory organs in particular; (b) tuberculosis is transmitted mainly through the sputum of the sick, which contains most tuberculosis rods; (c) books can relay the danger of infection, when the reader coughs or sneezes upon the book: therefore, do not cough or sneeze upon the book. (5) Be rigorous in not turning pages with fingers wetted with spit. Published by the Czech Provincial Relief Association for Lung Disease Victims in the Kingdom of Bohemia.”

Koch’s discovery of tubeculosis bacteria and the mechanism of infection proved the argument of the germ theory of disease. Koch did not convince everyone: yet most physicians and public health officials heard his concept as a call to “war on microbes.” TB spreads by droplets of sputum coughed out by people with infected lungs. Dried sputum particles in dust and on surfaces do contain bacteria. Today we know that these are unlikely to cause infection. Still, health workers around 1900 did set out to kill germs wherever the latter fell. Spittoons and signs prohibiting spitting were introduced to stop the spread of disease, first in factories and public baths, later on public transport and all public places of assembly.

But if spit and slobber convey infection, anything touched by the saliva of the sick is dangerous. If readers lick their fingers as they turn the pages of books, do public libraries become sources of pestilence?

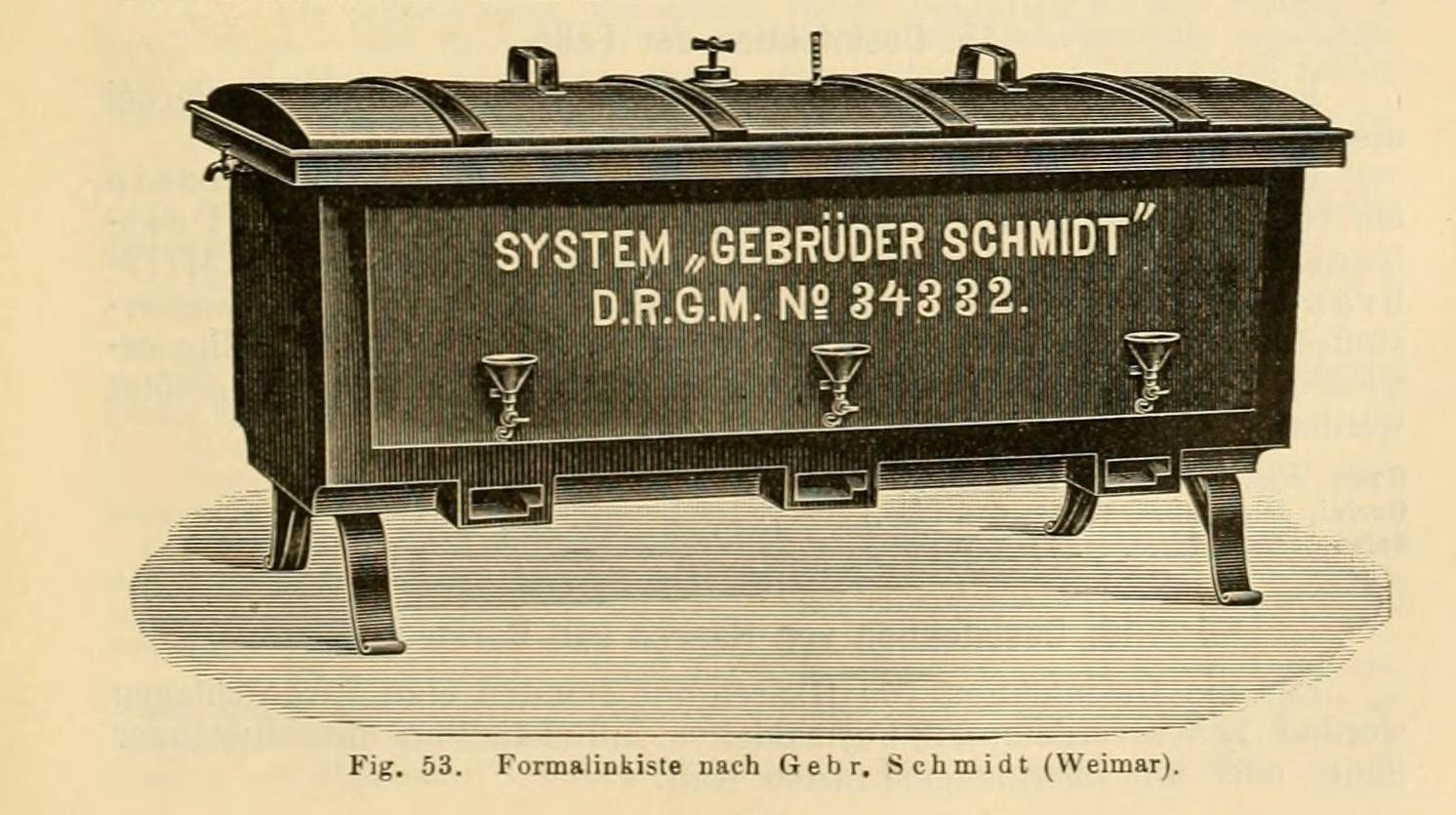

Studies on the presence of harmful bacteria in books were published from the 1890s, in Germany, Austria, England or the US. Boos perused by the sick were to be destroyed or disinfected; public library books had to pass through formalin vapours regularly. The Budapest hygienist Arthur Krausz found out that formalin destroys germs only on the surface of books and devised an apparatus for steam sterilization. Leather-books suffered greatly, but “such damage and loss are petty compared with the advantages of fumigation,” especially since “we do not find such luxurious tomes in rental offices and school libraries, with which we are most concerned, while clothbound books passed the procedure almost undamaged.” In 1902, the Berlin City Hall delivered a sizeable amount of books from public libraries to the Infectious Diseases Institute of Robert Koch, requesting them to be tested for bacteria, especially tuberculosis. The lung specialist Jon Mitulescu (1875-1942) demonstrated the presence of active bacteria in old, well used books with worn and wet pages in particular. Formalin was of use only when pages could be disinfected individually: larger libraries with faster turnaround of books should rather replace much handled volumes with new ones. Above all, the “people should be educated” not to lick fingers when turning pages or when counting cash. Before touching a borrowed book, “not knowing whose hands had handled it,” one should wash hands carefully with soap.

In the Czech lands, the Provincial Committee of Relief Associations for Lung Disease Victims, which connected Czech and German speaking TB associations, took up the issue in 1908. The Board of the Committee suggested on June 26 that well-worn, distasteful volumes be discarded and that every user wrap borrowed books in paper covers. A leaflet should be stuck upon the frontispiece of each library books, instructing on “the dangers of infection, tuberculosis in particular, conveyed and spread through books, on coughing and sneezing at the book and turning pages with fingers wet with spit that multiply this danger, as well as on the pertinent statutes.” The Governor Office passed this appeal to all public libraries, expressing its hope that privately run lending offices and reader groups will abide by it as well. District physicians were assigned control: in the future, no library license would be granted to applicants who did not follow the rules.

An identical prescriptions was issued by the Bohemian School Council in June 1909. The sticker printed with “Reader, Beware” was printed and distributed by the publishing house of the Provincial Teacher Union Association in Prague. However, this instruction reached only school libraries. The risks of disease may have been the greatest for pupils, but the TB relief groups wanted to reach a larger library audience.

Prague Municipal Library Building in the Years 1903-1926. The new building housing the library today was opened in 1928.

The Czech Relief Association for Lung Disease Victims published and distributed its own leaflet, selling 100 pieces for 70 haler, a little cheaper than the teachers’ publisher. The leaflet was available at the Association offices and from its secretary, Dr. Ferdinand Friedl (1854-1930). The Medical Museum collection includes two books with the Relief Association sticker. The popular brochure on Infectious Diseases written by the Prague district physician Dr. Karel Bulíř (1868-1939) had been originally held by the Vinohrady City Public Library. The 1912 book on the Ideals of Science and Religion by Jan Váňa (1847-1915), a high school professor and poet, had belonged to the student library of the Realgymnasium in Hradec Králové and its student residence hall. (The latter was named after John Amos Comenius: a student jester changed the stamp to Comedium at some point.)

In February 1910, the bacteriologist Ivan Honl (1866-1936), later the President of the Association, published a long article in the Narodni listy daily, entitled “The Book and the Infection.” If contaminated apartments are carefully disinfected and food can only be sold in fresh paper bags, he wondered, how come that people let books and journals that have passed through many hands into their homes? Disinfecting books without harming them may be difficult, but it is not impossible: paperbacks can be cleaned with steam, clothbound volumes with sublimate solution and formalin. It is, however, much more practical to stop lending books altogether, especially not to families affected by infection. Where this is not possible, libraries must guarantee hygiene and regularly discard and disinfect their volumes. Publishers and booksellers can make the greatest difference in promoting public health: by reducing book prices, they would allow even less prosperous families to purchase new books. Posters in libraries and stickers in the books must caution the readers on the nuisance of finger-licking and the duty to wash hands before and after reading.

Formalin Chest manufactured by the Schmidt Brothers (Weimar), recommended by Honl as most suitable for book disinfection. Theodor Weyl, Handbuch der Hygiene, 9. Band, Aetiologie und Prophylaxe der Infektionskrankheiten (Jena: Gustav Fischer, 1900), 995)

In the new Czechoslovak Republic after 1918, the Relief Association’s leaflets were dispensed by the Masaryk League against Tuberculosis, a voluntary association closely linked with the state. At the Plenary Assembly of the League in May 1924 Dr. Václav Cedrych (1897-1945) proposed issuing new library stickers with a shorter text. The Ministry of Education requested reducing the format as well. In 1925, several hundred thousand were allegedly published. Many books to which they were affixed have been since discarded. Hundreds if not thousands of them still exist somewhere. They remind readers of good manners when handling books, as well as the disease that inspired reading etiquette. A disease, it should be said, that has by no means vanished from the world.

Thanks to post-war vaccination campaigns, tuberculosis in Czechoslovakia has ceased to be the scourge it once was. Our account of hygienic warnings in library books is a local one, limited to the Czech lands or at best, to Central Europe. Do you have a different story of TB and books? Write to us!