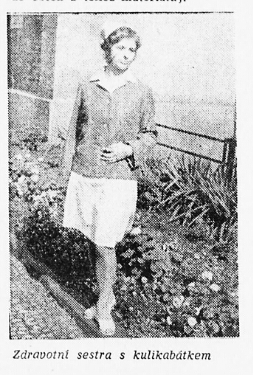

Kuli-kabátek (Coolie-Coat), early 1980s

Until mid-1980s, during patient visits or while playing outside with children patients, Czechoslovak nurses wore “coolie-coats.” The shapeless box-cut and hard fabric called forth no enthusiasm and nurses preferred their own sweaters or coats. In addition, there was always a shortage of coolie-coats, as well as other parts of the nursing uniforms. Textile factories were unable to respond to innovations and new designs and materials rarely made it to production.

The term coolie coat (Czech, kulikabátek) referred originally to a coat of Oriental origin or design. Since the 18 century, the pejorative word “coolie” (kuli) was used for an Asian indentured worker. Loose-fitting, straight, hip-length “coolie coats” of the 1920s-1950s fashion had side pockets, wide sleeves and a stand-up collar; they were buttoned in front and tied with a belt. In Czechoslovakia, coolie-coats were first advertised in the mid-1950s.

Overcoat in place of the sweater, in Jarmila Roušarová a Marta Šindlerová, „Protective Wear for the Health Worker: Accessories,“ Zdravotnická pracovnice 7/6 (1957), 375-377: 375.

Around 1960, the “coolie coat” became a part of the nursing uniform. In the 1950s, nurses had to buy warm coats themselves. Beginning probably in the “Institute for the Mother and the Child” in Prague, nurses procured “short overcoats made of thick, white or light blue flannel or terry-cloth. These coats fulfill their function if they are worn only in cold temperatures and outside, if they are washed regularly and, of course, worn only when on duty.” (…) Short coats were intended replace colorful sweaters, neither unified not hygienic, that nurses tended to wear over their protective suits.

Towards the end of 1960, ŘEMPO – the state company responsible for working clothes distribution in the public sector – opened an exhibition of protective wear for the health professions, including dark grey outdoor coats and grey, woven coolie-coats for nurses. An instruction of the Health Ministry issued in July 1960 assigned several coolie-coats per department, enough to assure weekly laundering and regular change of clothing. Nurses were not enthused: a magazine article reports that “experience prefers coats of good flannel or washable faux fur, below waist, with large pockets to warm hands, wide front band and loose sleeves with no cuffs.”

S. Holicka, the Head Nurse of the Karlovy Vary Health Services, added drawings to her designs the coolie-coat and other nursing outfits made of the “silon” textile. “How do you like it?” Zdravotnické noviny 16/29 (20.7.1967), 6.

In Czechoslovakia, early 1960s coolie-coats were made of Okonel, a cheap, soft, thick cotton-and-wool union fabric. The material wore out quickly and lost color. In 1966, Czechoslovak nurses tested the Aratex unwoven fabric developed by the Kolora Company in Semily which, however, pills, ladders and falls apart when frequently washed. Kolora did modify the fabric and ŘEMPO, together with the state Institute for Continuing Education in the Health Professions drafted a new design. The modified coats had no pockets (there were pockets on the apron after all), turn-up cuffs on the sleeves, V neck and small buttons; a warmer version made of duplicate fabric was designed as well. The nurses Jarmila Roušarová and Marta Šindlerová continued to insist on “thick, blue-grey flannel made of the best cotton… Why should it be so difficult for ŘEMPO to obtain some? In the last years, the regular market has been saturated by flannel spreads in so many pastel colors, with sheets for children printed in various animal patterns.”

In 1967, the Health Ministry announced a “thematic task” to design new clothes for mid- and lower-level health workers (nurses and nursing assistants), including clothes for colder days, family visits etc. The very first letter elicited by the poll in the Zdravotnické noviny (The Health Newspaper) weekly described coolie-coats as “unsightly and almost unusable when washed. Besides, there are not enough of them.” Simple, long sleeved coast dress should be war enough. Other suggestions included two versions of the dress, thin for the summer and insulated for the summer, long colorful coats for pediatric nurses and white coats for out-patient clinics. The writers agreed that a warm coat is a necessity for colder days, but proposed other designs: coats padded with polyurethane foam (Molitan), long-sleeved coats with lapels, a collar and sew-in pockets decorated with flaps, or a variety of styles according to body shapes. Suggested materials include light blue terrycloth, easy to sterilize, as well as the newly introduced Esterlin fabric woven from flax and polyester thread.

A nurse in the coolie coat, 1974. Photograph by kind permission of the author, dr. Bedřich Taláb. Zdravotnické noviny 28.3.1974, 5.

The Assessment Committee of the Ministry evaluated the proposals in May 1968 and passed them to health institutions for appraisal. The approved collection developed designs from the Jeseník Hospital, the Bast Fibers Research Institute in Šumperk and the Moravolen flax factory in Šumperk. Cotton and Polyester/Flax materials should “blaze with colors” from light green through a variety of blues to grey and pink. Different colors labeled different health profession and ranks. The “Kuryr” (Courier) marketing center in Pardubice assumed the distribution: at least for this once, samples were promised in “unlimited amount” to all applicants. The tests did not go well: synthetics generated electrostatic charge and precluded sterilization by boiling. An Instruction passed by the Ministry in January 1974 toned down the “blazing” and introduced “coolie-coats” made of the Arctic brand cotton fabric: beige for nurses, including pediatric nurses, midwives and women’s health nurses and dieticians, blue for medical and dental technicians and nursery assistants. The new coats, however, won no more favour with the health-workers than their predecessors did.

After mid-1970s, “coolie-coats” vanish from the pages of the medical press. They did not vanish from the reality of nursing: in some health facilities, nurses were issued with coolie-coats well into the 1980s.

Thanks are due to all those who helped us with advice on the “kuli-kabátek” story: all mistakes, however, remain ours.