Object of the Month: May 2020

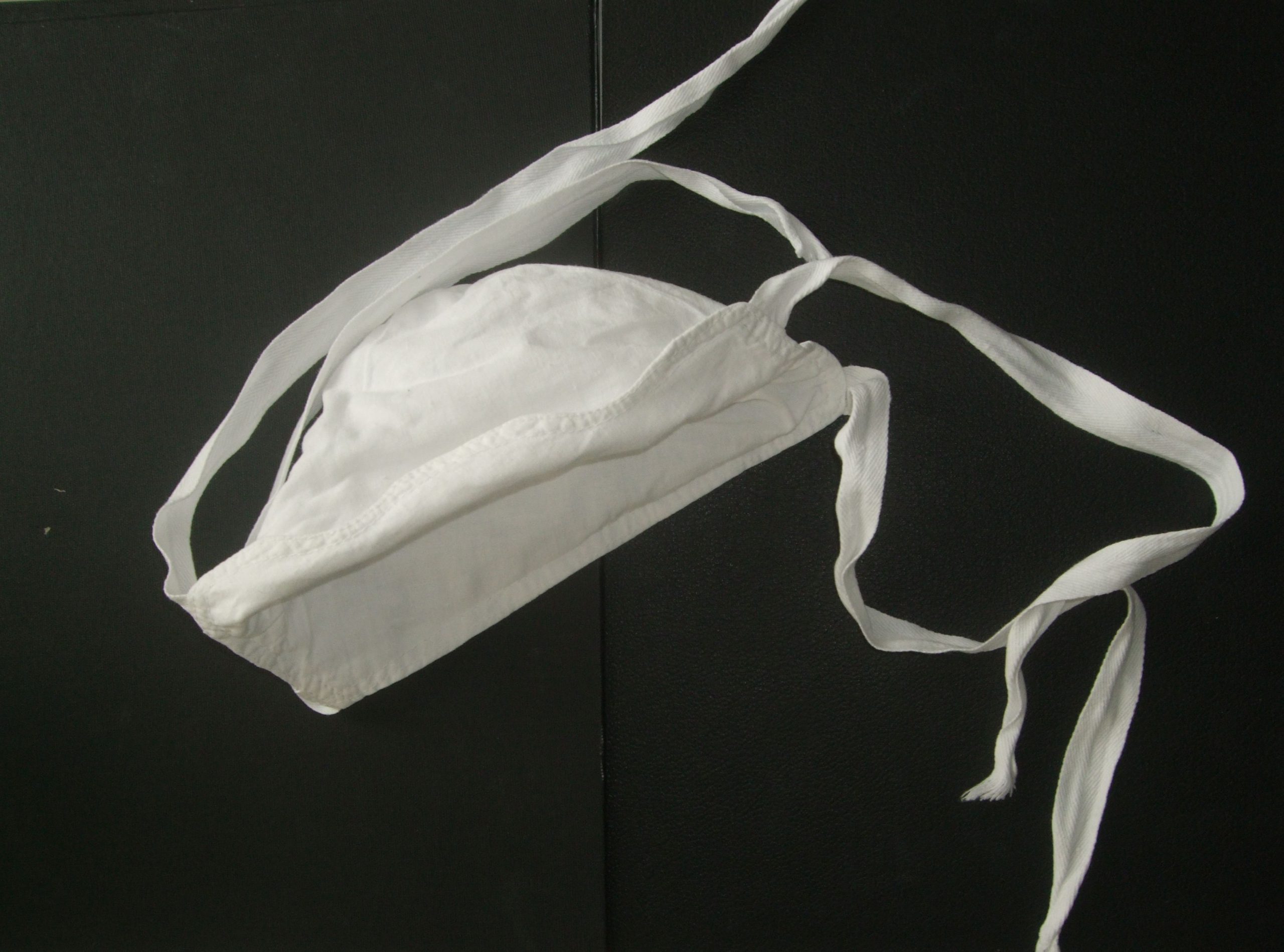

Surgical Face Mask, 1970s- 1980s

Masks we have used during past three months and continue to use to protect our fellow human beings and ourselves during the pandemic, were originally intended for medical personnel. Face masks were introduced to stop the spread of droplet infection beyond operation theatres, maternal wards and hospitals during the pneumonic plague epidemic in Manchuria in 1911. During the “Spanish flu” pandemic in 1918-1920 many cities and local authorities – the Swiss city of Lausanne, certain regions and cities in USA and Canada – attempted to introduce obligatory mask use in public transport or in contact with the ill.

Operation theatres saw first surgical veils and masks in the 1880s. During the last 130 years dozens if not hundreds of models came into being, striving for the most effective and at the same time most convenient construction, but their basic form was established by the early 20 century. A change was brought about by the introduction of disposable masks beginning in the 1960. The textile masks many of us wear and many have made for their families and others in need often return to the early models.

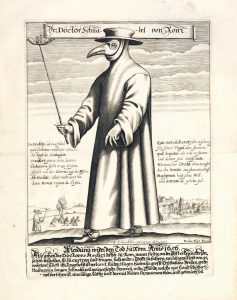

During plague epidemics of the 1700s, if not earlier, doctors used oiled gowns and sponges soaked in vinegar, held to the nose and mouth, to guard themselves against „bad air,“ the miasmas believed to cause the disease. Masks with a „beak“ filled with sweet-smelling herbs, garlic or rue, best known from 18 century German prints, protected the doctor as he approached the sick, while freeing his hands for work.

During plague epidemics of the 1700s, if not earlier, doctors used oiled gowns and sponges soaked in vinegar, held to the nose and mouth, to guard themselves against „bad air,“ the miasmas believed to cause the disease. Masks with a „beak“ filled with sweet-smelling herbs, garlic or rue, best known from 18 century German prints, protected the doctor as he approached the sick, while freeing his hands for work.

Since late 19 century, the aseptic mask covered the surgeon’s face primarily to protect the other person, the patient. Beginning the early 1900s the sick themselves, TBC patients above all, were directed to wear these masks as well. Pasteur’s discovery of microscopic disease agents inspired both antisepsis, the use of disinfectants to destroy harmful germs and later asepsis, the effort to keep the surgical wound, site and theatre bacteria-free in the first place, found its justification in bacteriology as well. Many devices we associate with surgery and surgeons- white gowns, gloves, metal instruments and apparatuses to sterilize instruments and garb – originate in this period. Gustav Adolf Neuber introduced sterile gowns in the hospital in Kiel in 1883, proceeding to separate septic from aseptic operating rooms and, in his own aseptic clinic, to build a system for sterilizing air. Numerous physicians turned attention to humans – the surgeon himself, his assistants and nurses and people coming to view the operation – as sources of infection. Washing hands with soap and alcohol became common across European and American hospitals, many clinics provided silk, cotton and later rubber gloves, sterilized together with aprons and gowns. Asepsis, however, was slow to take hold: to many, consequent organization of the surgical environment, limits to access, hygienic controls and compulsory uniforms appeared superfluous if not ludicrous.

Surgical masks were introduced by the Breslau (Wroclaw) surgeon Johann Mikulicz-Radecki (1850-1905) in mid-1890s. Mikulicz strove for maximum certainty of aseptic procedures. Bandages and instrument were handed to the surgeon directly from the sterilizing drum, students or visitors could enter, if at all, only in long coats and rubber shoes .Another possible source of infection, the body of the patient, was covered by sterilized cloth. Together with a local hygienist, Carl Flügge (1847-1923), the author of experimental works on droplet infection, Mikulicz pointed out the spread of bacteria in talking, coughing or sneezing, and insisted that sterile veils (Mundebinde) made of one layer of gauze, were attached to the cap and covering mouth, nose and beard. The Swiss ophthalmologist Otto Haab (1850-1931), who had started operating cataracts in 1883 under a glass plate, became an enthusiastic supporter of the Mikulicz mask. The sentiment was shared by many, but by no means by everyone.

Modifications introduced in the next twenty years aimed at making the masks more effective, but also more comfortable for its wearer. Triple veil of one gauze layer designed by Oskar Witzel (1856-1925) covered both head and face, leaving only a horizontal slit for the eyes. Especially in warm weather, the surgeon wearing it sweated profusely and could not breathe easily. K. A. Schuchardt (1856-1901) suggested a mask made of two straps of gauze (for head with hair and for mouth, nose and beard), affixed on the top of the head with a metal bow. Sturdier masks were uncomfortable and often required a nurse’s assistance when donned. For use in small interventions – ear, eye or teeth surgery – a light mask attached with a rubber band or temples of glasses, with a veil covering the mouth and the nose, was designed by the dental surgeon Otto Eichentopf (1874- 1931).

Mikulicz’s assistant Wilhelm Hübener tested the effectivity of masks in the lab. He found that masks that cling to the nose and the lips easily become wet with phlegm and become a supply of germs. Hübener covered the wire basket from a chloroform mask with a double layer of gauze. The basket hung from the nose above and its bottom edge fitted the chin. Doubling of the fabric and setting the mask at a distance from the face reduced the amount of germs exhaled.

Simple, unsupported masks of double cloth, bound around the ears and the neck with two ribbons, remained the most common. In most Czech

hospitals, they became current by the 1930s. The decision whether to use them depended, however, on the head of the clinic or the department. Pictures taken at the Prague Czech surgical clinic in the last pre-war years show everyone present covering their mouths and noses. In other hospitals, mask were considered unessential and were rejected.

No face mask can contain all germs and the less than 100% effectivity often discouraged their use. At a surgical conference in 1941, the pathologist Antonín Fingerland, head of pathology department at the Hradec Králové hospital (1900-1999), described a 1930s nosocomial infection at the local surgical department. A surgeon suffering from rhinitis infected at least 7 patients, five of whom died. The double layer mask failed to prevent the infection. The case excited much reaction, inspiring, on the one hand, new designs of the face mask, on the other hand confirming the suspicion of some surgeons that the mask, a source of much discomfort in warmer seasons, cannot guard the patient against germs. Masks should be either complemented or replaced by „quiet surgery“, prohibition of speaking during surgery and communication by gestures, which had been suggested by Mikulicz himself.

Surgical Department, Slaný District Hospital, around1953. NML Medical Museum Photo Archives, FA 3641.

In the first post-war years, Czech and Moravian hospitals tested many models of the mask. Ideal face mask should effectively filter bacteria, while allowing free breathing and releasing excess heat, permitting use for an extended time. Successful test did not, however, lead directly to mass production and use. When did surgery without face mask become inconceivable in the Czech Lands, remains unclear. It has been suggested that on the world scale, only the more effective and lighter disposable masks available since the 1960s silenced the foes of the face masks. In Bohemia and Moravia, disposable masks spread much later and the original cloth masks, sterilized with heat, remained common until the 1990s.