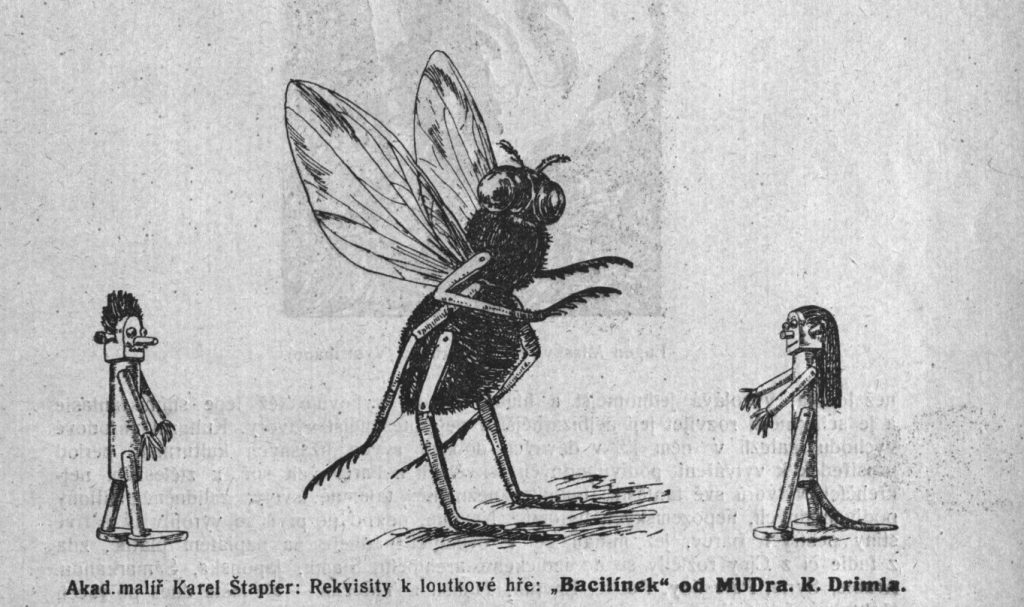

Karel Štapfer, painter, illustrator and head stage designer of the National Theater in Prague, designed the first Bacilínek puppets as well as the cover of the first print edition. Karel Driml, Bacilínek: veselá tragedie pro malé i velké o zdraví a nemoci o čtyřech jednáních s předehrou [Bacilinek: A Cheerful Tragedy for Children and Adults on Health and Disease] (Choceň: Tiskárna “Loutkáře” spol. r.o., 1929). National Medical Library/ Medical Museum Library, MA 4381

Object of the Month: January 2021

Bacilínek

On its web pages and on facebook, the Chrudim Puppetry Museum has shared the stage music composed by Miloš Smatek (1895-1974) for Jan Malík’s 1950 production of Bacilínek. Thank you!

https://www.puppets.cz/cs/aktuality/nahravka-z-archivu-bacilinek

In the second half of the 19th century the work of John Snow, Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch (1843-1910) demonstrated the role of germs as agents of infection. The turn of the century saw also an unprecedented expansion of campaigns of disease prevention and public and private hygiene, driven by public welfare organizations, state agencies, as well as makers of cleaning products for the home, the body and the mouth. Health education took up all available media. Images and stories of monstrous bacteria as villains and health workers or detergents as heroes fought tuberculosis and sold toothpaste. Readers and viewers related to human beings the monsters attack and the heroes save, teach and lead.

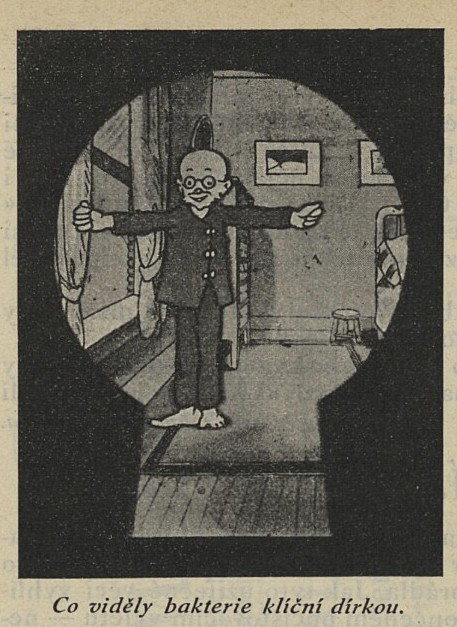

What did the bacteria see through the keyhole: from the film Jinks, Měsíčník dorostu Červeného kříže [Red Cross Youth Monthly] 4/5 (1924), 67.

Early in the new century, germs entered both the silver screen and the stage. In the 1920s and 1930s, the London Health and Cleanliness Council fought infection and promoted clean homes with rotoscoped films featuring Giro the Germ. Aboard a fly, Giro enters homes, multiplies and does harm. Already in 1919, the New York Bray Productions studio produced an animated film titled Jinks for the Brooklyn Committee on Tuberculosis. The title character loses his job due to disease, is rejected for life insurance and visits a doctor only when compelled by his wife. When he returns, he has a terrifying dream: a “sportive germ” of tuberculosis named Mike Robe decided to settle in Jinks’s lungs and start a family. The germ and his fiancé marry in a discarded tomato can and with their progeny, numbering thousands, set off towards their new home. Jinks wakes in terror and begins his reform right away: inhaling deeply by the window, exercising strenuously and getting a thorough physical exam. When the bacteria see this, they explode in panic. The National Tuberculosis Association distributed the film through commercial theaters, schools and public lectures, as well as travelling productions using a projection truck. The League of Red Cross Societies lent the film to Czechoslovakia and beginning in 1920, the Red Cross and the Masaryk League against Tuberculosis screened it at health education events and in schools under the title “Pan Brouček” (Mr. Bug). The film does not seem to have survived in the US or in Europe and the names of its makers are unknown today.

The Czechoslovak 1920s drive against TBC made use of other films as well, but for the countless puppet theater enthusiasts in pre-war Czechoslovakia, educational theatre performances held much greater appeal. A key author of „plays with purpose“ on health themes was the hygienist Karel Driml (1891-1929), whose 1922 Bacilínek (Little Bacillus) play remained a fixture of professional, amateur and school puppet stages at least until the 1960s. After graduation from the Czech Medical Faculty in Prague and war service in the navy, Driml received a Rockefeller scholarship to study public health at the Johns Hopkins University. Having returned from Baltimore, he became an official of the Ministry of Public Health. He was a dedicated puppeteer from his high school years. Driml wrote dozens of plays: both Bacilínek and Začarovaná země (The Enchanted Land, 1922) deal with tuberculosis, a play titled Brok and Flok (dog names) with preventing rabies (1923), Špiritár aneb pekelný alchymista (Spiriter, or, the Alchemist from Hell, 1929) with alcoholism. Other plays directly promote soap brands, life insurance or Thymoline toothpaste. His characters and plots develop those of traditional puppet theater, but reflect the contemporary world and introduce new objectives. Puppet germs appear both in Bacilínek and the toothpaste promotion play Budulínka bolí zoubek (Budulínek has a toothache, 1924).

Driml also wrote the screenplays for several films on health subjects, directed by Josef Kokeisl (1894-1951): Procitnutí ženy (Awakening the Woman, 1926, „an unique epic on female hygiene“), Perníková chaloupka (Hansel and Gretel, 1927), Kašpárek a Budulínek (Punch and Budulínek, 1927) on dental hygiene, V blouznění (Enraptured, 1928) on the benefits of insurance, the comedy Pramen lásky (Spring of Love, 1928) promoting the Poděbrady spa, Stín ve světle (Shadow in the Light, 1928) on trachoma, as well as Popelka (Cinderella, 1929).

Driml may have recognized the value of puppets for health education during his time as a Rockefeller scholar. The campaigns to fight alcoholism and tuberculosis financed by the foundation in the US and, since 1919, in France, did use puppet shows as well as travelling exhibitions, brochures or films. The French performances featured the traditional Guignol (Punch): a play written by Henri de Gressigny on the dangers of TBC and alcohol use was performed across France between 1919 and 1923 and was seen by hundreds of thousands of children. According to Driml, however, the Jinks film was the direct inspiration for Bacilínek. In the play, the witch Jedubaba summons Belzebub, the Devil, asking him to create a curse that will harm humankind in the epoch of modernity and progress. The Devil creates Bacilínek, a creature so small to be invisible, and The Fly, which will carry him, as it did Giro, into every home. The character of the Fly, which appears also in the 1922 Enchanted Land, links infection to dirt, oblivious to most common means of TBC transmission.

The wife of the poor cobbler Dratvička (“Twine”) from Hloupá Lhota (Sillyham) fell ill with TBC. The whole family with four children lives in dirt in one room, lacks money for a doctor or good food, trusts harmful potions sold by a quack, and what money the cobbler makes, he spends on drink. Just like Mike Robe, Bacilínek plans to settle in Dratvička’s lungs with his wife and kids. A long dialogue between Dratvička and Škrhola (a classical simpleton puppet character), full of mishearings and puns familiar from traditional puppetry, demonstrates the dullness of both villagers. At that point, a puppet troupe arrives with Kašpárek (Punch) at the helm, who tries to show them the right path. From the papers, Kašpárek has learnt on Robert Koch’s discoveries, visits the scientist in Berlin and makes the acquaintance of the tiny animals that cause consumption. The Punch and the Doctor then set out to spread enlightenment „to the people, to schools, towns and simple dwellings, to air their rooms, to teach them to live well, to drink milk and to love fresh air and sun. “ The third act returns to the cobbler’s shack: his wife has died and the quack woman tries to impose the harmful regime that killed her on Dratvička as well. Kašpárek and the Doctor enter, Koch examines the cobbler and prescribes clean water from the pump, the scent of the wood (fresh air), enough milk and eggs in place of brandy and cleanliness. In the last act, Dratvička is „all new“: he drinks milk, sits in the sun and exercises in the „Sokol“ gym. When Bacilínek sees his metamorphosis, he despairs and commit suicide, followed by his wife, as well as the witch Jedubaba.

The play premiered on August 16, 1922 at the Social Care Exhibition in Brno co-organized by Driml and was published the next year by the Loutkář (Puppeteer) journal in Choceň. Follow-up social care exhibitions in Moravian cities featured the play as well. With a 1923 decree, the Ministry of Public Health recommended using the play and other works of Driml for promoting public hygiene, giving Bacilínek an official stamp of approval. The play was published again in 1925 and translated into Slovak, German, Serbian and Dutch languages. In Serbian, a version for blind readers was brought out as well. In Czechoslovakia, hundreds of theaters and troupes put on Bacilínek: Sokol, school or military ensembles, local Red Cross and Red Cross Youth units and local sections of Ochrana matek a dětí (Mother and Child Protection), but also semi-professional theaters including Loutkové divadlo Umělecké výchovy (Art Education Puppet Theatre) in Prague with Jan Malík (1904-1980) in 1935, the Kašpárkova říše (Punch Kingdom) in Olomouc in 1937 or the Divadelní studio (Theater Studio) of Antonín Turek in Brno beginning in 1938. In 1929, the Red Cross- affiliated Divadlo mládeže (Youth Theater) performed Bacilínek with living actors, under the direction of Miloslav Jareš (1903-1980).

Theaters, including the Turek studio in Brno or the Theater of Anna Sedláčková in Prague, continued to stage Bacilínek in the years of the

Bacilínek, a marionette by an unknown maker after Karel Štapfer’s design, Moravia, 1920s-1930s. Collection of the Moravian Museum. We thank dr. Jaroslav Blecha for making the pictures available to us.

Nazi occupation. In the summer months of 1944, the play in German translation was performed by girls living in the TBC housing for children in the Theresienstadt ghetto (Kinder Erholungsheim Südstrasse 1), directed by the pediatrician Arnošt Podvinec (1900-1948). Most actresses that appeared in this Bacilínek did not live for another year. Of this version of the play, only the prologue has survived. According to this fragment, the play, put into verse by Driml, was adapted by another doctor (Podvinec) „properly to target our current situation. “

The interest in Bacilínek did not drop after the war either: the puppet stage of the Central Army House staged it in 1947 for the benefit of flood victims and in 1950, Jan Malík took up again his pre-war productions in the Central Puppet Theater in Prague. The premiere took place on June 25, 1950. In 1951, the Olomouc New Puppet Stage followed. The original 1922 puppets of Bacilínek, his wife and the Fly, figures not readily available on the market, were designed by the stage director of the National Theatre, the painter Karel Štapfer (1863-1930) and his drawings inspired many later marionettes, without limiting the puppeteers’ invention. Malík’s 1950s productions used wayang puppets moved from the bottom, common in Czechoslovak professional puppetry in that decade. The problem of Bacilínek’s size, easily solved in animated cinema, gave rise to many creative arrangements. Usually, the puppet was smaller than its fellows, but big enough to communicate with them. Driml recommended framing the germ with a circular light on the wall, suggesting microscope images. Malík presented changes in size by combining the puppet with projections and illuminated props.

Karel Štapfer, návrhy Bacilínka, Bacilínky a Mouchy, Loutkář VII/7 (1923). Karel Štapfer, designs of Bacilínek, his wife and the Fly, Loutkář VII/7 (1923)

During half century of Czechoslovak history and the development of health education, Driml’s „puppet tragicomedy: underwent many changes as well. We know only little about revisions made by directors. In the third print edition published in 1929 Driml himself made small changes and added a lecture for schoolchildren titled “Your worst enemy: tuberculosis.” Later editions published by Jindřich Veselý (1885- 1939) and Jan Malík were much more substantial.

The spiritus movens of pre-war Czech puppetry Jindřich Veselý brought out Bacilínek in prose, with many verse dialogues. The book came out in 1930 in the Prague Vojtěch Šeba publishing house, with illustrations by painters and puppeteers Vít Skála (1883-1967) and Ota Bubeníček (1871-1962), intended as a tribute to recently deceased Driml. Veselý inserted passages from other plays by the hygienist, his publicity slogans, stories of his educational work and plots of his films, as well as chapters from history of medicine and hygiene „for older schoolchildren“ and a short history of Czech puppetry. Driml appeared in the narrative itself, taking the place of Robert Koch.

Vojtěch Cinybulk, frontispiece, Karel Driml, Jan Malík, Bacilínek: Veselá tragedie pro malé i velké o zdraví a o nemoci (Praha: Umění lidu, 1950)

In his 1935 production, Jan Malík introduced, besides Bacilínek, germs of children’s diseases such as diphtheria, typhus, influenza or smallpox, highlighted the educational tone of several dialogues by extra verses and added an optimistic quatrain at the end of the play. In the new print edition published in 1950, he followed Veselý in replacing Koch with Driml and added interludes with a narrator’s commentary. Smaller changes in the text reflected – not enough for some reviewers – the new social atmosphere of the late 1940s and early 1950s. The character of the Devil sheds any religious connotations, the Punch finds reports of medical discoveries in an unspecified newspaper, rather than the rightwing Národní politika stopped in 1945, and presents himself to the doctor as „Punch, the young pioneer!“ Gone is the remark on expensive medical care as the cobbler’s reason for going to the quack; on the other hand, the play mentions farmers accused of feeding milk to pigs instead of meeting obligatory milk deliveries. Villagers have debts „at the pub, “ rather than „with the Jew“: the expression may have become intolerable to Malík after the war. In his concluding technical remarks, Malík proposes puppet designs and scenic and sound innovations derived from his own practice, but also accents ideological changes: “Dratvička is a type of village proletarian, who arrives at consciousness in the course of the play. Škrhola, on the other hand, should have the features of a nagging village prattler and perhaps even a reactionary kulak.”

For some early 1950s critics, Malík’s revisions were far from satisfactory. A post-

Bacilínek, a marionette by an unknown maker after Karel Štapfer’s design, Moravia, 1920s-1930s. Collection of the Moravian Museum.

performance discussion among artists, writers and teachers, organized in the Central Puppet Theater in 1950, opened a politically charged debate. Vlasta Brychtová reacted to the play’s publication with a scathing review in the cultural section of the Lidové noviny paper. In her view, both Driml and Malík ignore the social context that gives rise to infections and with „bourgeois hypocrisy“ seek their origin in illiteracy and alcoholism. Young viewers are shown the village as a world saturated with superstition, a world of ignoramuses and drunks, at a time when it begins „profoundly to change, when culture, intentionally withheld by the bourgeoisie, begins to pervade the countryside. “ With little justice, Brychtová attacks the characters of the witch and the devil, the episodes of conjuring and charming (which, to Driml, often represent science in the genre of fairy tale) as well as macabre scenes that terrify the young audience. (In his commentary, Malík emphasized that Bacilínek and his wife must remain negative characters, but there is „no place for terror, no frightening tone or spectacle can appear in the play“.) Erik Kolár (1906-1876) defended Bacilínek in Lidové noviny in 1951. He admitted that the play passes over social causes of tuberculosis, but appreciated the continuing role of Driml’s play in the struggle for healthy way of life, its display of contemporary milieu, science and the scientist in puppet theater, as well as the place of Malík’s productions in the making of new 20 century theater. Kolár suggested continuing the debate: it is, however, unclear to what extent Bacilínek remained the object of open controversy.

The Central Puppet Theater staged the play at least until mid-1950s; in the early 1960s, the play remained on the repertoire of amateur theaters. Did various stages continue to put on Bacilínek later? Did the 1950s debates influence the shape of later productions? We will be thankful to our readers for their recollections of Bacilínek, from whatever time they may come.

Šimon Krýsl

Punch and dr. Koch in an unknown performance of Bacilinek. Karel Driml, “Puppet Plays Teach Health to Czechoslovak Children,” The Nation’s Health 7/6 (1923), 464-465, 464

Vít Skála, Bacilínek and Bacilínka (Bacilínek: Pohádka [Bacilinek> A Fairz Tale] (Praha: Vojtěch Šeba, 1930)