Fornax Chemical Heater, 1940s. NML Medical Museum, P 165. ⌀ 6,7, height 2,3 cm. Photography by Veronika Löblová

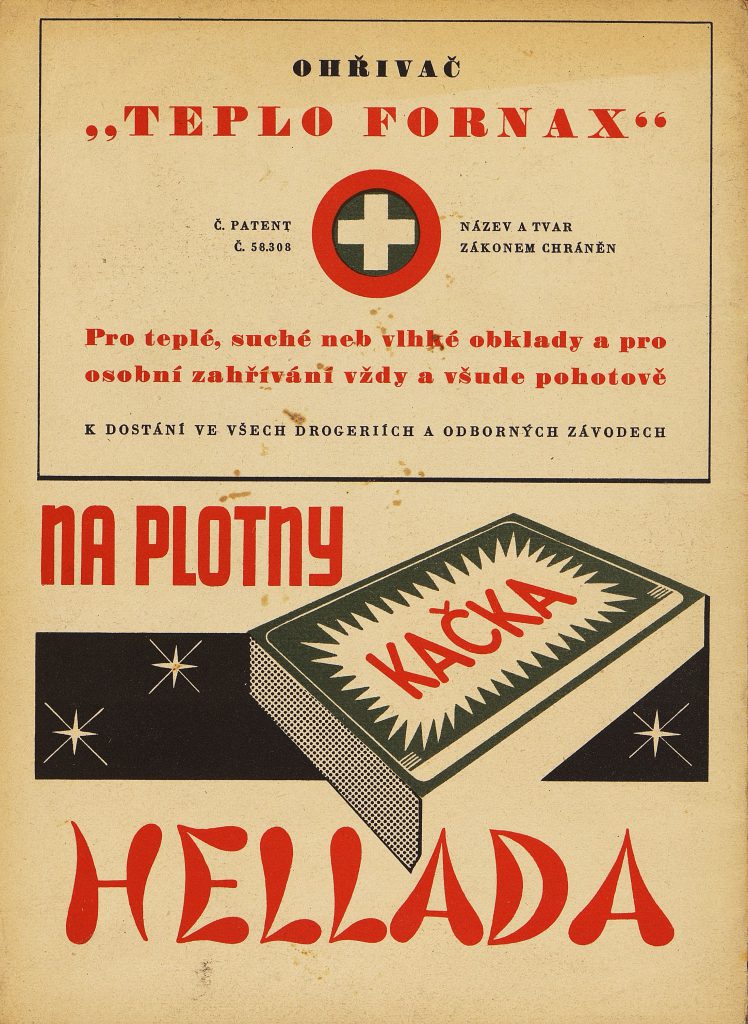

Teplo-Fornax

Winter is coming and staying. To heat both the bed and the body, hot bricks and stones had been used and in the 16 century metal hot water bottles were introduced in Europe. The early 20 century saw the birth of the electric blanket, which transforms electric current into heat. All these sources of heat could serve to alleviate pain and to provide comfort for the ill. What else provided warmth to people during history?

Alongside fire and electricity, exothermic chemical reactions deliver heat. Two small metal objects in the Medical Museum are an example of the use of chemical warming for relaxation and treatment. Hollow, rotund doses with attached ribbons and two apertures covered with perforated plates may resemble earpieces or hearing aids. The opening on the side serves, however, to fill the dose with liquid or powder. The opening on the top surface has a double lid and shifting the inner plate opens and closes twelve little holes, controlling the air supply inside the dose. On the top surface the world Fornax, Latin for chemical or alchemical furnace, is imprinted.

The Fornax cases are indeed small chemical furnaces, in which adding water generates heat. They could serve to relief sore limbs, to warm a bed or to prevent hypothermia in a person injured in the snow. The mix of chemicals could be placed in a metal box or even an impregnated bag: when water was added, it oxidized quickly, releasing heat. The precise composition changed in the course of the 20 century: it contained powdered iron with manganese, copper or magnesium compounds.

The Fornax cases are indeed small chemical furnaces, in which adding water generates heat. They could serve to relief sore limbs, to warm a bed or to prevent hypothermia in a person injured in the snow. The mix of chemicals could be placed in a metal box or even an impregnated bag: when water was added, it oxidized quickly, releasing heat. The precise composition changed in the course of the 20 century: it contained powdered iron with manganese, copper or magnesium compounds.

Under the brand name “Teplo Fornax” (“Heat-Fornax” or Heat-Stove”), chemical heaters were made from 1938 till the late 1940s in the Czech Town of Kolín by Pavel Just (1900-?), the director of the local branch of the well-known Hellada soap factory and the son in law of the factory owner, František Kadlec. The heaters were sold both in pharmacies and in drug stores. Pavel Just bought the patent in 1938 from Marie Gutwirth, of whom we have been able to find no further information so far. He registered the trade of “patented heater manufacture” on December 29, 1937 and started production in the Hellada factory in Kolín-Zálabí. The production ceased in 1945– probably due to the damage to the factory in an air raid – but began again later that year. In 1938 Just was granted a trade license for the “sale of soap, toilet and cosmetic products” as well, but as the Hellada production did not resume after the Liberation, he could not return to this line of work.

In October 1934, Marie Gutwirth filed for a patent on a composition based on cast iron filings and ammonium chloride. The powder was mixed first with acidified water and then with water and lime and left to react. The patent was granted in August 1936. Having bought the rights, Pavel Just probably adjusted the recipe: according to the Codex-Agrol chemical and pharmaceutical catalogue published by Antonín Vydržel in 1941 and 1946, Fornax according to Pavel Just contained 92% powdered iron, 2% copper sulfide and 5% copper sulfate, all diluted with wood flour. The Little Manual of Chemical Technology, Pharmaceutical and Drugstore Practice by Jaroslav Kopš (1916-1991) lists yet a different prescription: about 400 grams of the Fornax mixture, containing powdered iron, manganese chloride, potassium permanganate and iron chloride, should be placed in impregnated bags. Adding 2-3 tablespoons of cold water heats it to 50-60° C and the temperature lasts for 3-5 hours.

We do not know when Fornax ceased to be produced. Teplo-Fornax is still mentioned in a 1965 skiing textbook, reprinted in 1971, as a chemical source of heat for an injured skier. This suggests that the product was still known in the 1960s. Chemical heat sources using metal oxidation continue to be used today: magnesium „flameless heaters“ for food preparation have been part of the US army equipment since the early 1990s.

For advice and information on the Fornax heater history we are thankful to Robert Jirásek and to Jaroslav Pejša from the State District Archives in Kolín.

“Teplo-Fornax Heater, Patent Nr. 58.308, Name and Shape Protected by Law. For Warm, Dry or Moist Compresses and Personal Warming Always and Everywhere Ready. Available in All Drugstores and Specialist Stores.” Advertisement for Teplo-Fornax and products of Hellada in the magazine Širým světem 14 (1944)