SARS-CoV-2 Plush Virus, GIANTMicrobes, 2020. NML Medical Museum Visual Art Collection, V 103. Photograph by Petra Vobecká

Object of the Month: December 2020

COVID-19 Plush Virus

Would you like a soft plush virus for your home?

The Connecticut-based GIANTMicrobes company, which had brought hundreds of cuddly germs – deadly, annoying, as well as beneficial – as well as figures of vitamins, human organs and diseases to the toy market over the last two decades, launched its red plush SARS-CoV-2 virus on March 19, 2020. A warm, cozy toy coronavirus may seem repulsive, tasteless or insensitive to some people: a few internet comments spoke of cynicism or making cash on a tragedy. COVID toys can, however, help children and adults to release stress, shake off anxiety and acquire knowledge. Confined in our apartments, working and learning from home and linked to the world by newscasts full of death, disease and dread, we can certainly use some such comfort.

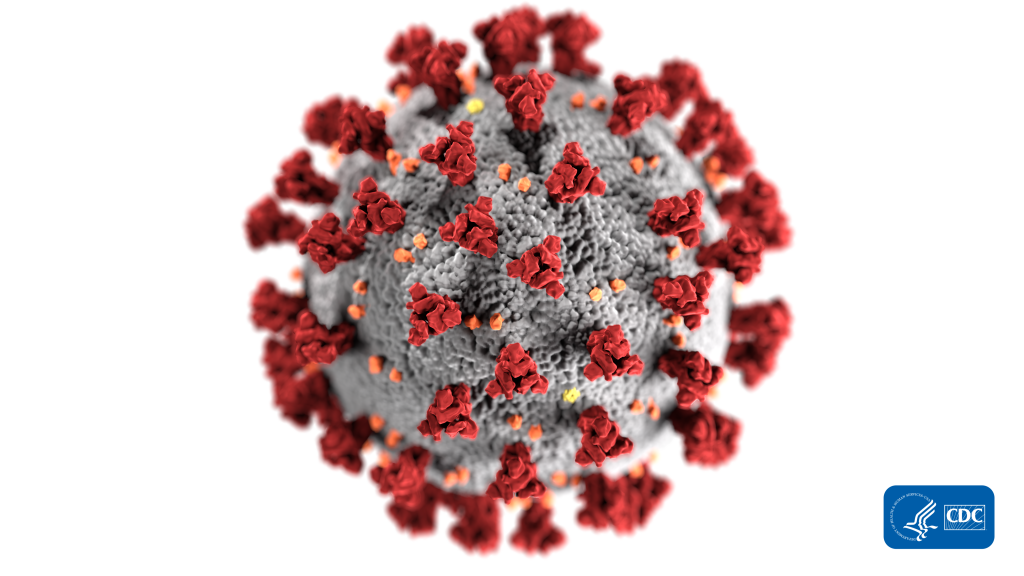

We know that “the coronavirus” causes a disease that has claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of people. But can we imagine a virus?  To understand how the infection spreads and how to protect ourselves and others, we need to accept that microbes are real, living creatures: that “the virus” is neither a shadowy power on an unstoppable course through the world, nor a weapon designed by one or another cabal in order to wipe out half of the world and dominate the other, nor a hoax used by those in power to keep us docile. Microbes have bodies and they grow, multiply and change just like other living things. Plush viruses may have big eyes and a hint of personality: otherwise, their shape corresponds to the creatures we see under the microscope. The look of the new coronavirus toy – in five sizes, complemented with cards with scientific facts – likewise derives from the micro-photographs and drawings issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

To understand how the infection spreads and how to protect ourselves and others, we need to accept that microbes are real, living creatures: that “the virus” is neither a shadowy power on an unstoppable course through the world, nor a weapon designed by one or another cabal in order to wipe out half of the world and dominate the other, nor a hoax used by those in power to keep us docile. Microbes have bodies and they grow, multiply and change just like other living things. Plush viruses may have big eyes and a hint of personality: otherwise, their shape corresponds to the creatures we see under the microscope. The look of the new coronavirus toy – in five sizes, complemented with cards with scientific facts – likewise derives from the micro-photographs and drawings issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

(An)drew Oliver (1970-), the founder of GIANTMicrobes, began designing and producing plush germs in 2001 as a student at the University of Chicago Law School. According to an interview published in the Nature journal, the seed of the idea was a passage in the 1985 book by the physicist Richard Feynman (1918-1988) Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! The author relates his astonishment watching paramecia (unicellular ciliates) through the microscope ocular lens. “The idea it’s mechanical, like a computer program – it doesn’t look that way. They go different distances, they recoil different distances […] they don’t always turn to the right; they are very irregular. It looks random, because you don’t know what they’re hitting; you don’t know all the chemicals they are smelling, or what. […] As the drop of water evaporated, over a time of fifteen or twenty minutes, the paramecium got into a tighter and tighter situation: there was more and more of this back-and-forth until it could hardly move. It was stuck between these ‘sticks’, almost jammed. Then I saw something I had never seen or heard of: the paramecium lost its shape. It could flex itself, like an amoeba. It began to push itself against one of the sticks, and began dividing into two prongs until the division was about halfway up the paramecium, at which time it decided that wasn’t a very good idea, and backed away.“ Protozoa, as well as other microscopic creatures, react to their surroundings and pursue goals: perhaps not with intent, but also not mechanically. Oliver had another, more practical incentive: the need to teach his children to wash their hands. How does one explain to a child why her or his tummy aches and how to prevent the pain? And finally, we find the ability of tiny and even tinier things to affect our world both fascinating and – often justly – frightening.

The first „giant microbe“ Oliver designed was the Common Cold (rhinovirus). Further plushies portrayed the agents of cholera, malaria or plague: with data on the diseases, their history and prevention on cards. In 2007, sixty different toys were made, in 2018, their number reached 400. At the end of 2005 the plush microbes were displayed among other creative responses to everyday dangers and anxieties at the exhibition Safe: Design Takes on Risk in the New York Museum of Modern Art. The presentation included more than 300 designs and products protecting „body and mind from dangerous or stressful circumstances, respond to emergencies, ensure clarity of information, and provide a sense of comfort and security.“ In the Czech lands, the GIANTMicrobes made an appearance at the 2011 exhibition Antibiotics – An Endangered Treasure of Humankind that showed both the history of antibiotic treatment and the contemporary dangers of antibiotic resistance.

The microbes, infused with much mischievous humor, do indeed protect minds full of worry for life, health and sustenance. At the same time, they help teaching children, young people and adults how to safeguard their own health and help others. New models were introduced during the ebola, SARS and MERS epidemics. The Red Cross employs plush red blood cells in programs encouraging blood donations; since 2019, the company has taken part in a campaign against the spread of sexually transmitted diseases, both by making herpes or chlamydia toys and financially. A part of the profits from the sale of microbes helps public health and public benefit agendas: the HIV virus toy sponsors amFAR (The Foundation for AIDS Research), the polio virus, designed to commemorate the anniversary of Salk vaccine in 2015, supports the Rotary Club’s drive for polio eradication. The sale of red COVID viruses contributes to the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases and other charities. GIANTMicrobes supplies its plush microbes also with face masks, similar to those worn by Playmobile or Igra little women and men or those available for Lego figures. Of course, we can put these mask on the snouts of non-infectious plush animals with which we bunk up during the pandemic. Yet they also „estrange“ the toy from the actual virus: a masked plush coronavirus is not a threat, but a helper in surviving and understanding hard times.

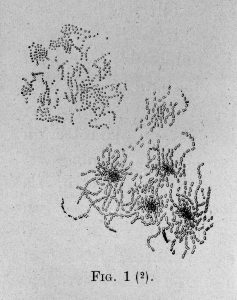

In public health education and training, anthropomorphic germs have a long history. The authors of oldest drawing of the microscopic world were captivated by the corpuscles, grains and rods as yet unseen: in 1864, Louis Pasteur took note also of the regularity and beauty of bacterial formations. His drawing of the „mother of vinegar,“ chains of bacteria in gelatin structures on the surface of fermenting alcohol, shows not only symmetry and elegance, but also creatures in active, if not purposeful movement.

In public health education and training, anthropomorphic germs have a long history. The authors of oldest drawing of the microscopic world were captivated by the corpuscles, grains and rods as yet unseen: in 1864, Louis Pasteur took note also of the regularity and beauty of bacterial formations. His drawing of the „mother of vinegar,“ chains of bacteria in gelatin structures on the surface of fermenting alcohol, shows not only symmetry and elegance, but also creatures in active, if not purposeful movement.

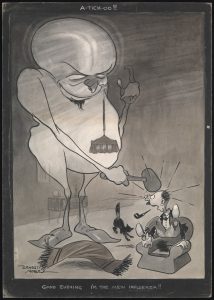

Towards the end of the 19 Century, the development of the germ theory of disease causation on the one hand and the  expansion of programs to prevent infectious, above all respiratory diseases on the other motivated a flood of drawings, prints and animated films in which monsters in the shape microbes with eyes and craving hands threaten frightened or unsuspecting humans. Both public agencies for disease prevention and producers of chemical disinfectants and tooth hygiene products published publicity materials starring germs in the role of villains. In the 1890s, a boy equipped with Calvert’s carbolic antiseptic vanquishes a tangle of tentacles representing various diseases; around 1910, the French Anios germicide defeats multiple monsters including mildew, typhus, tuberculosis or plague. Germs soon conquered the silver screen as well: the 1920a and 1930s saw rotoscope animations featuring Giro the Germ, produced by the London based Health and Cleanliness Council. Aboard a fly, Giro invades homes, multiplies and causes harm, before soap and electricity take him prisoner.

expansion of programs to prevent infectious, above all respiratory diseases on the other motivated a flood of drawings, prints and animated films in which monsters in the shape microbes with eyes and craving hands threaten frightened or unsuspecting humans. Both public agencies for disease prevention and producers of chemical disinfectants and tooth hygiene products published publicity materials starring germs in the role of villains. In the 1890s, a boy equipped with Calvert’s carbolic antiseptic vanquishes a tangle of tentacles representing various diseases; around 1910, the French Anios germicide defeats multiple monsters including mildew, typhus, tuberculosis or plague. Germs soon conquered the silver screen as well: the 1920a and 1930s saw rotoscope animations featuring Giro the Germ, produced by the London based Health and Cleanliness Council. Aboard a fly, Giro invades homes, multiplies and causes harm, before soap and electricity take him prisoner.

Czech puppet plays of the same time feature the fairy tale Bacilínek character, conceived by the physician Karel Driml (1891-1929): also in the saddle of a fly, this „invisible, insidious bandit“ invades lungs and spreads tuberculosis. The charming animated sequence by H. L. Roberts, included in the fifteen minute film „Goodbye Mr. Germ“ (National Tuberculosis Association, 1940), the bacillus in a top hat remembers the many lungs it has infected, before the introduction of sanatoriums, X-rays and tuberculin tests bring his campaign to an early end. In the 1950s, Lysol keeps away flocks of sharp-fanged terrorists, while in the next decade, a plump microbe and his friends cannot withstand disposable cups for rinsing the mouth. In Colgate commercials, comic book „invisible nasties“ continue to harm teeth and gums in full color today.

Czech puppet plays of the same time feature the fairy tale Bacilínek character, conceived by the physician Karel Driml (1891-1929): also in the saddle of a fly, this „invisible, insidious bandit“ invades lungs and spreads tuberculosis. The charming animated sequence by H. L. Roberts, included in the fifteen minute film „Goodbye Mr. Germ“ (National Tuberculosis Association, 1940), the bacillus in a top hat remembers the many lungs it has infected, before the introduction of sanatoriums, X-rays and tuberculin tests bring his campaign to an early end. In the 1950s, Lysol keeps away flocks of sharp-fanged terrorists, while in the next decade, a plump microbe and his friends cannot withstand disposable cups for rinsing the mouth. In Colgate commercials, comic book „invisible nasties“ continue to harm teeth and gums in full color today.

The red plush germ may bet he most successful coronavirus toy introduced this year, but it is by far not the only one. During the state of emergency, three sisters from the German town of Wiesbaden designed the Corona board game, in which rivals hunt for foodstuffs for a neighbor in isolation. In the Pandemic game, introduced in 2008 and inspired by the SARS pandemic, the players cooperate to eradicate diseases and find new medicines. The game has long been a bestseller, but the 2020 emergency measures duly enhanced its popularity. Other Corona games were invented in India and elsewhere. Available Corona action figures probably target older audiences. Crocheted amigurumi toys appeared in Japan in the 1920s and became a hit in the 1980s, after 2000 spreading far beyond its land od origin. Many artists offer crocheted viruses as toys, pendants, stress balls as well as Christmas decorations.

In the early 21 century, our world is shaped by the media and filled with virtual monsters and images of actual horrors. Sometimes we find it difficult to tell the former from the latter. Could pre-war animated infectious bogeymen still motivate us to change? Even if they could frighten us, would we not believe rumors and hoaxes more than reason and science? Soft teeth of a plush wold do not scare, but warn against the sharp fangs and strong jaws of real wolves. Fluffy spikes on the plush virus body caress – and at the same time, they illustrate proteins viruses use to catch hold of the cells and cause infection. The plush virus reports danger and provides comfort. We do need both to speak of the pandemic to each other, to learn, to shelter, to play and to overcome.